By Offer Brener

How to Design and Build Hope

Hope isn't something that just happens; it's something we create. In uncertain times, designing hope becomes a powerful act of leadership and vision. It’s about turning...

Read MoreOur job at Firma is to help organizations rethink why they do what they do. We encourage them to surprise themselves with the answers they come up with, and then we work with them to turn these answers into a work plan. Each time we do it, we begin with a series of exercises: some meant to help us think open, some meant to help us think focused. When the Israeli Association of Community Centers asked us to perform 25 such processes in 12 hours, we decided to go about it a bit differently: to give our clients the tools to do it themselves.

*

In a moment I'd like to speak with you about an event-branding workshop that we've recently delivered to 50 people with zero experience in branding or design. I'd like to walk you through what we did with them, why we did it, and how we emerged 12 hours later with 25 outlines for playful, surprising, moving and multi-layered events. But first, I want to ask you to join me on a quick memory exercise.

Try to think back on one event that you've attended in your lifetime which truly made you feel. The birthday party of kindergarten friend. Your high school graduation. Your wedding, or someone else's. A yoga retreat. A political demonstration. A music concert in a large arena, or in a small coffeeshop in a foreign city. Perhaps a football match. Perhaps something else.

Now try to think of a very bad event. A place that you got to and immediately wanted to leave. Something about it felt awkward, or unpleasant, or not quite right. Perhaps the room was too vacant? The acoustics too poor? The evening entertainment programme was too long? Perhaps you thought, never mind, let's make the best of it, and headed to the bar, and the person serving drinks was young and handsome in a manner that made you feel unyoung and unhandsome, and it was clear that the evening is over.

Now think of an event production process. What happens froms the moment the idea is first conceived until the doors open? What sort of things may be keeping the producer up at night? Budget, probably (how to get it, how to divide it, how to accommodate unexpected expenses that plummet along the way). Logistics is also a notable sleep-depriver (when do the folding chairs arrive? Did David remember to print out the signs?). Then there's marketing, of course (how many people are going to come? How much money will we have to spend for them to come?).

This circus act of a to-do list ultimately translates into hundreds of details, and these details, in their turn, translate into an experience – memorable, not so memorable, enjoyable, not so enjoyable. The trouble is that in between the budget acrobatics and logistic pyrotechnics, we don’t always have enough air left to ask ourselves what kind of experience we want to create.

*

Last October, we hosted a workshop for 50 representatives from community centres all over Israel. The common: they all wanted to put together meaningful events in their communities, and they were all facing challenges. In 2019 it’s not easy to get people excited about a community event; in many cases, even shiny big-budget commercial event will have a hard time scraping them away from their Netflix or Fortnite. With this setting as a starting point, waking up every morning and striving to create meeting opportunities for communities can become challenging at best and Sisyphean at worst.

Some of the workshop participants came to us in real distress. Others arrived curious, with some successful events in their past which made them eager for new tools that can help them to create richer events. In both cases, the combination of limited budget and hunger for independence gave birth to a creative solution: instead of harnessing our own strategists and creative teams to brand these events, we tried to give the community centre staff the tools to think like strategists and creative teams themselves.

We split into groups. Each group chose an event they'd like to examine and develop. We began.

The first half of the day was dedicated to thinking inwards. Our premise at Firma is that at the base of every brand there's one core idea - one insight that is the base for everything that's to follow. The main challenge is to find the right insight. There’s a clever phrase we sometimes refer to, which argues roughly the following: "No one buys a drill because they want a drill. They do so because they want a hole. And in fact, they done want a hole either - they want a shelf or a painting. And honestly, they don't want that either - they want a home". Events aren't much different. When we choose to get ourselves off the sofa and out of the house, the true reason for it is almost always broader than the event itself.

After several hours of dense thinking exercises (in an ordinary branding project, this phase can take up to several months) we've arrived at sombre, stirring and hopeful insights.

Two participants from a community centre in a distressed neighbourhood realised that the street fair they have been working on can't settle for offering joy and excitement. Those may work very well for established neighbourhoods, but what their community needs from a fair is first and foremost relief: a chance to rest, a pause from the constant race of survival, a break. In another corner of the room, a participant looking to address the needs of the LGBTQ youth in his periphery neighbourhood arrived at the conclusion that his event's story cannot end with community solidarity, but must also consist of official establishment recognition. Another participant, who had been planning for several years to host a musical event at the central bus station of her city, suddenly realised that her story is not at all about music, but about transforming a loud and hectic stop-on-the-way into a space that invited people to dwell, to get to know the people they share this space with, to feel as if they're crashing at a friend's living room.

The process of focusing inwards was over. We had lunch. Then we began re-opening.

When handled properly, a simple core idea can grow to astonishing heights. Ideally, it can create a whole new space with its own set of distinguishable rules. For instance, it can define the way that this event uses language: is it humorous or serious? Sarcastic or naive? Does it speak with us at the eye level of an adult or a child? Does it sound like a speech or a story? A good core idea can also give guidance to the way the event interacts visually: a potluck invitation coloured in soothing green is utterly different than an invitation in magenta pink, not to mention an invitation in black and white. A public protest that publishes itself through pictures of its distinguished speakers is a very different occasion than a protest which promotes itself with photos of the social reality it aims to change.

Yet developing a core idea doesn't end with what the event may looks and sounds like. It can be a decision making method which affects dozens of touchpoints that give the event it's sensory depth.

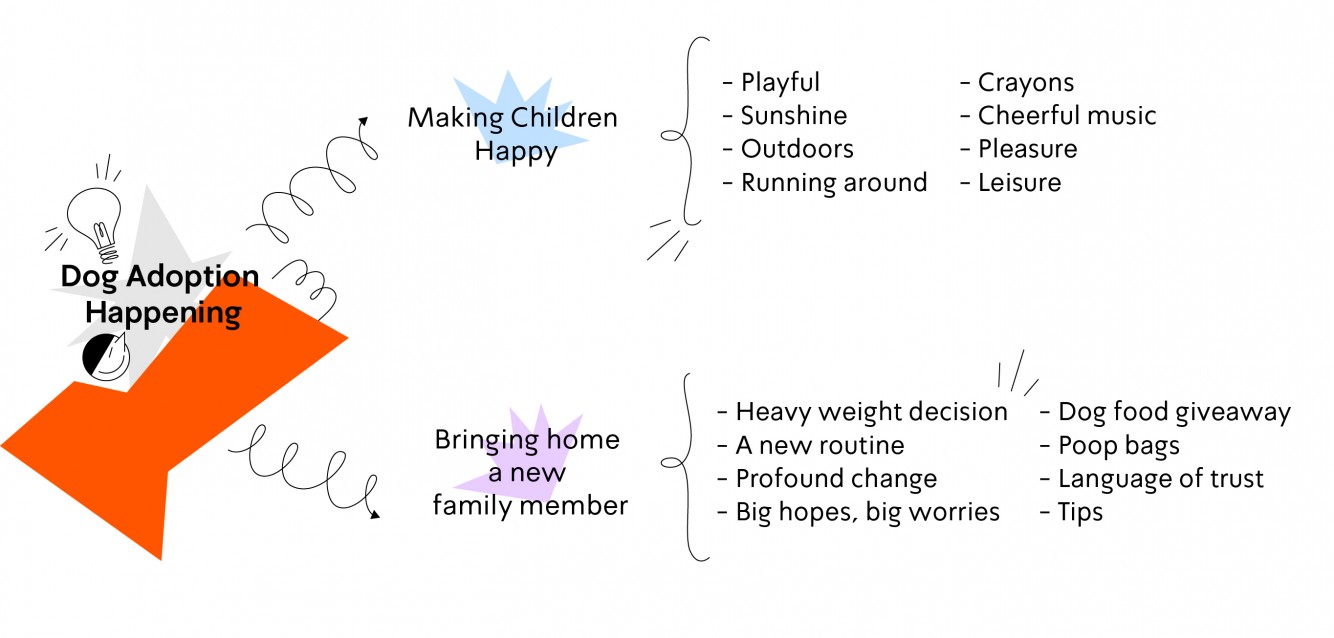

Let's take, for instance, a dog adoption happening. If its core idea is "making children happy", we can choose to hold it outside, in a place that calls for romping and running around. We can also design an invitation that conveys a sense of outdoors and sunshine, play cheerful music, write down the names of each dog in crayons and in easily readable capital letter, and hand out drawing papers and colours to invite the children to draw pictures of the dogs.

However, if the core idea is "bringing home a new family member", we're now looking at a significantly different event. We may choose to walk around the neighbourhood and slide our invitation underneath people’s doors, so that their first encounter with our event wil literally be in their own homes. We may want to design them in the form of a family photo with a dog in its centre, or to illustrate the dog already settled in their new home. The words we use will have to convey trust – unlike the “making children happy” version, this event’s story is no longer about pleasure and leisure. It is now a about a heavyweight decision that our audience is contemplating which can profoundly affect their lives, and we need to find ways to engage with their hopes as well as their worries: perhaps we can give away small bags of puppy food for the first few days? Give tips for managing adjustment difficulties? Hand out poop-bags? It's not that people don't already have bags, nor are they incapable of googling tips, but making them a part of the event is a way of saying "we're here to talk to you about your new routine, not about a fantasy".

At the end of the day, the events we remember - unlike the ones we forget, and the ones we wish we'd forget - are measured in their ability to speak with us about the things that genuinely matter to us. When they succeed, it's almost always thanks to two things: having a meaningful core idea, and knowing how to develop in into an all-engulfing experience – through words, through design, through the hundreds of details that constitute the event before, during an after.

This is no less true for brands that aren't events. Sometimes we meet them in the form of Nike, Apple, Google or Mercedes Benz, but much more often than that we meet them in the form of the Hebrew University, Sapir College, Ichilov Hospital, Hatikva neighbourhood, the city of Holon, the Occupy Rothschild protest, Benjamin Netanyahu, B’Tselem, Beitar Jerusalem. Whether global or local, whether commercial, public or social, brands are always about the story behind. At first glance, they may look like the outcomes of our 12 hour workshop: a name, a symbol, a logo, a system of words and fonts and colours that makes the brand identifiable. But truthfully, these icons and logos are merely a way of giving structure to an emotional conversation that is silently taking place between people and brands all the time: the set of hopes, expectations, associations and gut feelings that arise in us whenever we look at the logo.

People always had and always will have these gut feelings. It’s up to us to decide: do we want to take the time to ask ourselves what sort of conversation we want to have with them, or do we want to let it form on its own. Perhaps you’ll join us one day for a workshop of question asking and brand making. Perhaps you won’t, and that’s cool too. In case you won’t, here are four simple steps you can try out yourself, even now as we speak:

First, try to briefly verbalize what it is that you do.

Second, try to find one refreshing insight about why you do it, or why someone else might find it meaningful. If you didn’t exhale “huh!” when you said it, keep looking.

Then, try to put this insight into the most precise words that you can.

and Now – close your eyes, try to imagine that this insight is your compass in every decision you need to make from now on. I don’t know what your current dilemmas are, but you do. Picture them one by one. Now try to solve them.

By Offer Brener

Hope isn't something that just happens; it's something we create. In uncertain times, designing hope becomes a powerful act of leadership and vision. It’s about turning...

Read MoreBy Firma - Change Matters

היא משנה למנכ"ל פירמה שהגיעה מעולמות העיצוב והמחול, אישה של אנשים שמעריכה את זמן האיכות שלה עם עצמה...

Read MoreBy Firma - Change Matters

זה התחיל ממענה פשוט לצורך בוער, וצמח לחברה גדולה שנמכרה במאות מיליונים. Morning, לשעבר "חשבונית ירוקה...

Read MoreBy Elad Mishan

I'm a runner. It's been a few years since I was bitten by that bug, and day and night it takes me towards my goal: in the biting cold, under the scorching sun, toward the dista...

Read More